Aggie Ring repairs and resizing via The Association temporarily paused. See full details

What in the heck is ‘Hullabaloo, caneck, caneck’?

There have been many wrong answers to “What does ‘Hullabaloo, caneck, caneck’ mean?”

The phrase is found all over Aggieland, most notably at the start of the Aggie War Hymn.

Some have claimed it’s the sound of a train running along tracks, or the sound of a cannon being loaded.

While those would be very fitting Aggie origins, the truth is less romantic: “Hullabaloo, caneck, caneck” is actually a version of a nonsense phrase that colleges all over the country used as a football chant more than a century ago.

At Texas A&M University, we’ve preserved it much longer than other schools did — probably because of its prominent use in the War Hymn, which was written in 1918.

And what does it mean? Well, “hullabaloo” is a legitimate English word meaning a noisy uproar, and “caneck, caneck” means absolutely nothing.

But it all came down to us from ancient Greek, believe it or not.

First, here are a couple more of the best stories

It’s been said that War Hymn author J.V. “Pinky” Wilson, Class of 1920, used the phrase because the thumping sound of World War I artillery reminded him of an older Aggie yell. (“Hullabaloo, caneck, caneck” appears in Aggie yell books as early as 1904.)

In 1972, Texas A&M president Dr. Jack K. Williams joked to a state legislative committee that "it is Chickasaw Indian for ‘Beat the hell out of the University of Texas.’”

To get to the bottom of this, we’ll need to go back and look at the ridiculous things American football fans were yelling in the late 1800s.

In the early days of college football, Princeton and Yale were among the first powerhouses, and their fans came up with cheers and songs that quickly spread to other schools across the country.

Two examples: In the mid- to late-1800s, Princeton students had a “locomotive” cheer, in which the students chanted syllables at an increasing speed, and a “rocket” cheer — this was the classic “sis-boom-bah” chant, based on the sound of a firecracker hissing into the sky and exploding, followed by spectators saying “ahh!”

Both of those chants made it to Texas A&M, where our “Locomotive” is still heard at every Midnight Yell Practice (“Rah rah rah rah, T-A-M-C …”), and there have been occasional attempts to revive the “Skyrocket” yell.

As you can see, many cheers had words or syllables that were chosen primarily for the noise they could produce.

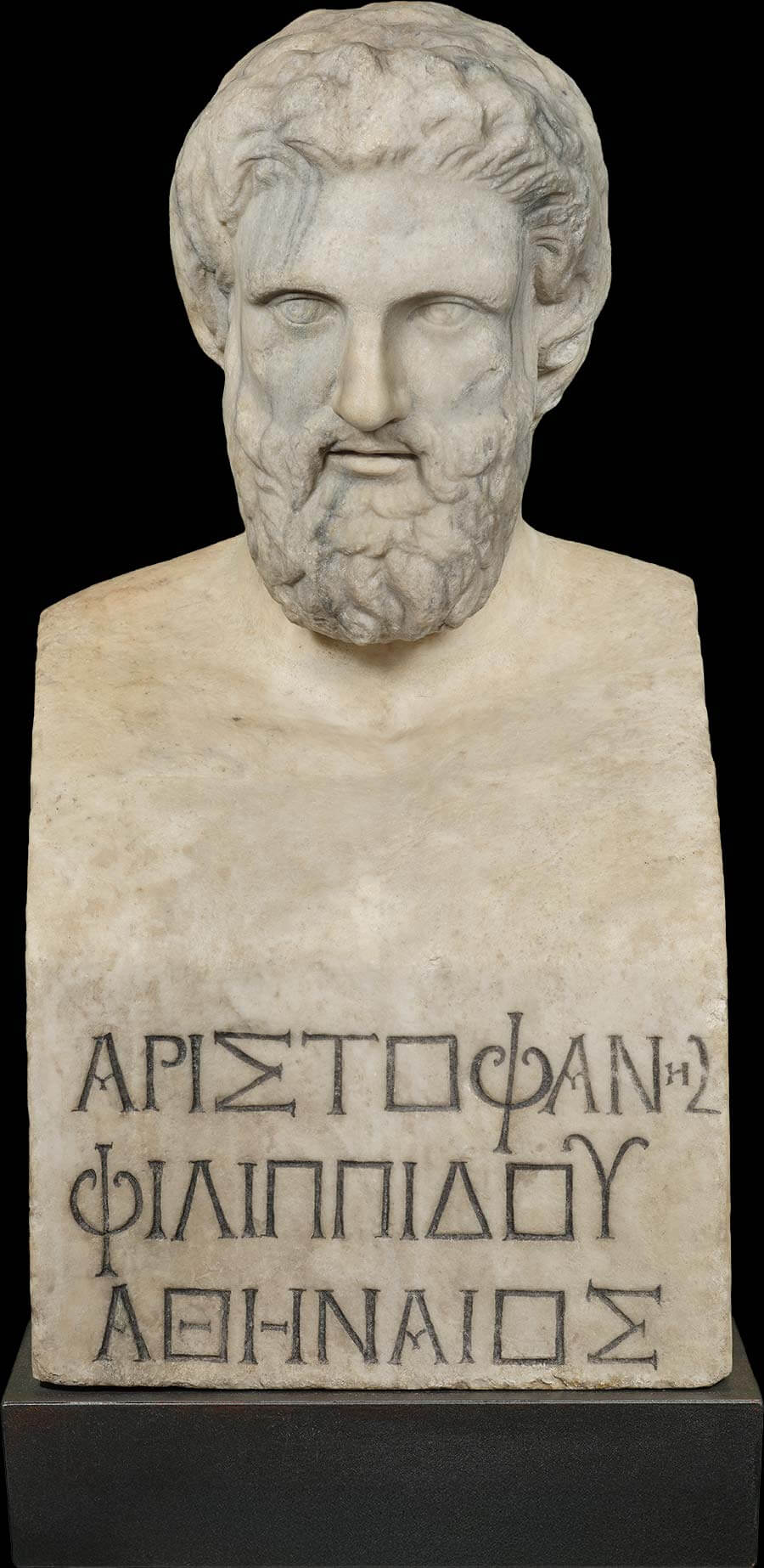

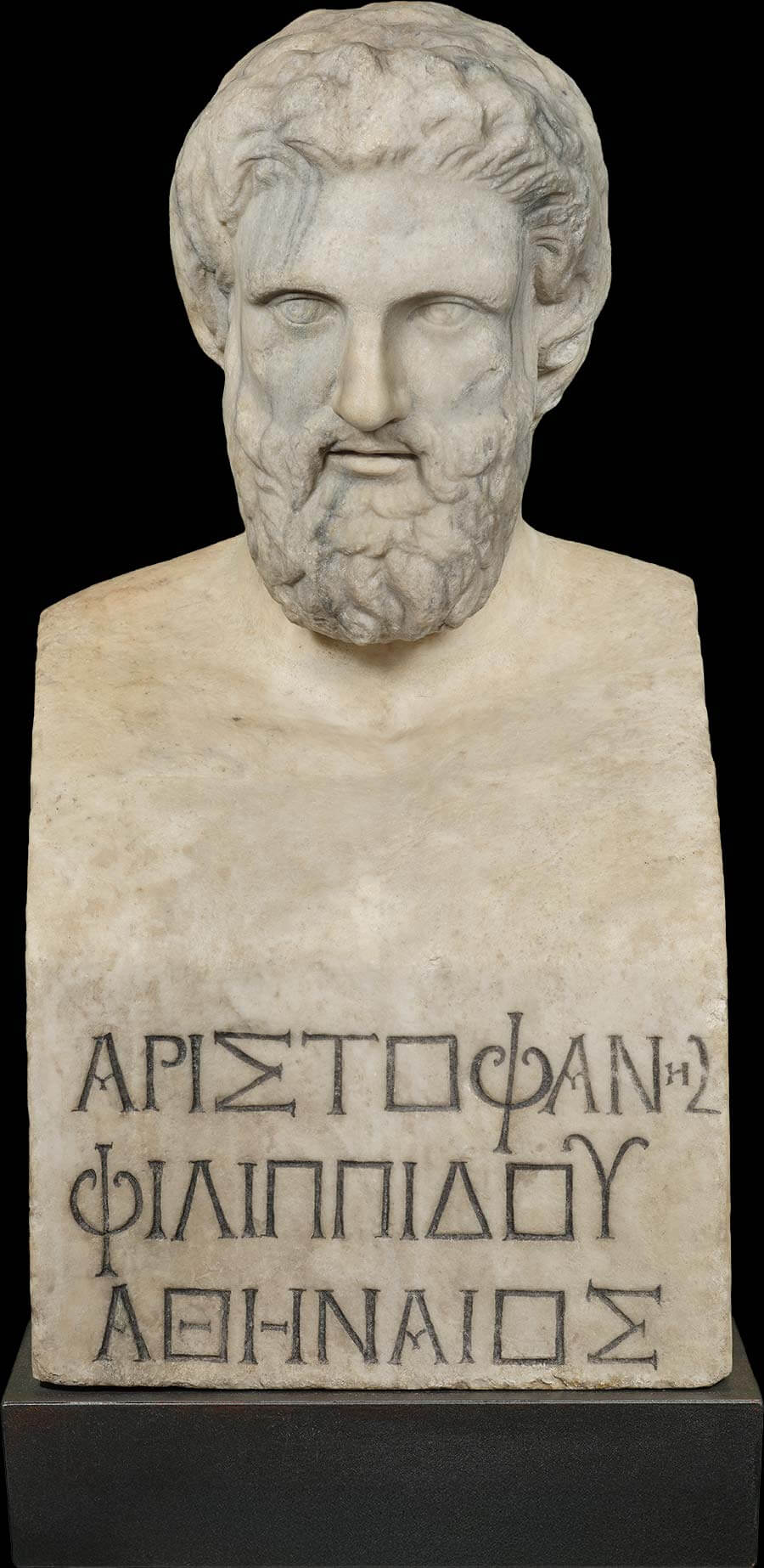

That’s how Yale’s “Long Cheer” took shape. In 1884, students took bits of Aristophanes’ play The Frogs — which had been a smash hit comedy in ancient Greece — and put the words into a cheer they used at a baseball game, according to Yale Alumni Magazine.

The cheer goes like this

The first lines are from the play, in which the Greek god Dionysus journeys to the underworld by crossing a lake in a ferryboat, serenaded by a chorus of opinionated frogs.

“Brek-ek-ek-ex, ko-ax, ko-ax” represents the frogs’ sound, much as we use “ribbit” in English. “Parabalou” is the ferryman’s command to bring the boat alongside the shore. After the cheer fueled a Yale baseball rally, it took off.

© Gabinetto Fotografico delle Gallerie degli Uffizi

Eight years later, in an 1892 almanac list of college cheers, you can see Aristophanes making his way across the fruited plain.

“Bric-a-ty Brax Co-ax Co-ax — Bric-a-ty Brax Co-ax Co-ax — Hul-la-ba-loo! Hul-la-ba-loo, Woo, ’Rah Ninety-two!”

“Hubla-le-luck, ko-ak - ko-ak; Hubla-le-luck, ko-ak - ko-ak; Wo-up, wo-up, Diabolou, Richmond!!”

“Brekety Kex Ko-ax Ko-oo, Brekety Kex O ’92!”

“Wich-i-Koáx, Ko-áx, Koáx! “Wich-i-Koáx, Koáx, Koáx! W.J. W.J. Boom!”

“Hul-la-ba-loo! Kenick Kenick. Hul-la-ba-loo! Kenick Kenick. Who's Alive, Ninety-five, Tiger!”

“Hullaballoo, Kanuck, Kanuck! Hullaballoo, Kanuck, Kanuck! Hoorah! Hoorah! J. H. U.!”

In 1912, long after “Hullabaloo! Caneck! Caneck!” was already in use at Texas A&M, the Aggie yearbook shows another variant of Yale’s “Long Cheer”:

“Alla-ca-zoo! Co-ax! Co-ax! Terra-orex-orex-orex! Hulla-baloo! Hulla-baloo! Aggies! Aggies! Rah! Rah! Rah!”

“Hellaballoo-conneck-conneck” appears closer to home in an 1899 Auburn yearbook, in a yell almost identical to the 1904 Texas A&M yell.

So the concept was definitely making the rounds, like the skyrocket cheer and indeed the entire concepts of organized yelling and male cheerleaders (nationwide, cheerleading began as an all-male endeavor).

It’s not surprising that it persisted at Texas A&M, where even today, students continue carefully passing down traditions to each other.

“Hullabaloo” is an actual English word that snuck in among the nonsense syllables, possibly because it was more familiar than “parabalou.” (It’s undeniably hard to get your Greek spelled right when it’s being yelled from the opposite bleachers.) Meaning a noisy uproar, “hullabaloo” dates back nearly two centuries; the Oxford English Dictionary cites “hollowballoo” in 1762 and “hallaballoo” in 1800.

There’s no direct line from “parabalou” and “ko-ax, ko-ax” to “hullabaloo, caneck, caneck.” But it seems our Aggie phrase might have started out as Greek for “Bring ’er to shore! Ribbit, ribbit!”

How to find Aggies in a crowd

The cadence of “hullabaloo, caneck, caneck” is so familiar to Texas Aggies across generations that all you have to do is honk, knock or otherwise sound it out to get a “Whoop!” in response.

Keeping Aggies connected

Gifts made to The Association of Former Students help us share Aggie stories and history, support current students and keep the Aggie Network connected.

Make a gift of any size to lend your support!

‘Hullabaloo’ rumble strips work at any size

In 2016 and 2017, some new markings appeared on roads around Texas A&M University’s campus, and Aggies soon discovered that driving over them at the correct speed produced the pattern of beats we’re so familiar with.

Though the strips have worn down over time, you can still hear the pattern in some locations (see map at tx.ag/HullabalooStrips).

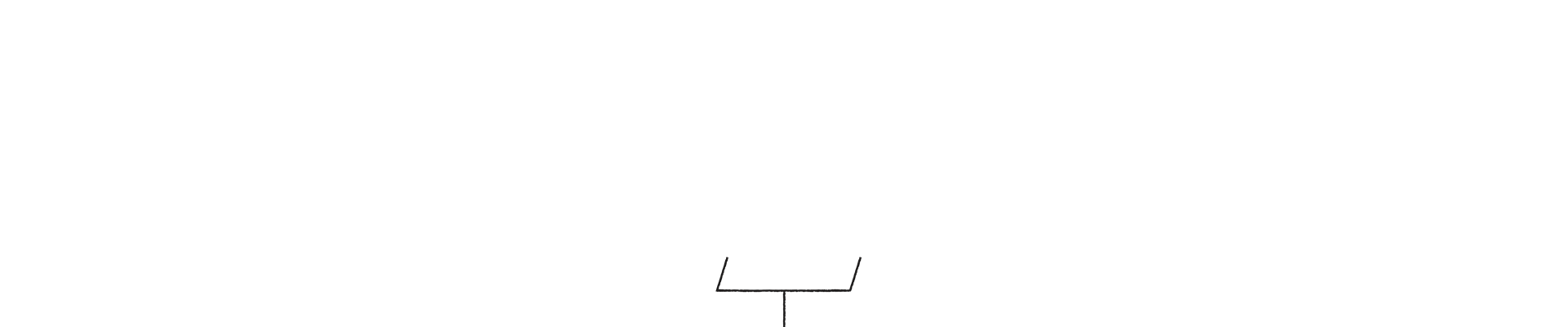

You can also make your own version; the math works for vehicles of any size!

Cary Tschirhart ’85, a former Aggie bandsman who helped work out the math for Texas A&M’s hullabaloo strips, shared instructions:

- Measure the wheelbase length (from center of front wheel to center of back wheel). This is the value of “x” below.

- Place the first two strips two wheelbase lengths apart (2x).

- Place a third strip 3x from the second strip — Repeat at 3x, 4x, 2x, 3x, and 3x.

- Roll the vehicle over the strips, and you’ll get “hullabaloo, caneck, caneck” twice, as at the start of the Aggie War Hymn.

wheelbase

For complete accuracy, the vehicle would need to move a specific speed to match the Fightin’ Texas Aggie Band’s timing. Visit tx.ag/HullabalooStrips to see how Tschirhart calculates that, starting with the fact that the Aggie Band marches at 104 beats per minute!